質數演算法比較

Prime Number Algorithms Comparison 2025: Which is Fastest?

Introduction: Why Algorithm Choice Matters

Not all prime number algorithms are created equal. Choosing between Trial Division, Sieve of Eratosthenes, Miller-Rabin, and AKS can mean the difference between milliseconds and hours of computation time—or between kilobytes and gigabytes of memory usage.

Real-world scenario: You're building a cryptographic system that needs to generate a 1024-bit prime number. Using naive Trial Division would take millions of years on a modern computer. Using Miller-Rabin? Less than 1 second. The algorithm matters more than the hardware.

This comprehensive comparison analyzes 8 major prime checking algorithms across key dimensions: time complexity, space complexity, accuracy (deterministic vs probabilistic), implementation difficulty, and real-world performance. Whether you're optimizing for speed, memory, or mathematical certainty, this guide will show you exactly which algorithm to use and when.

New to prime numbers? Start with our Prime Number Check Complete Guide for fundamental concepts before diving into algorithmic comparisons.

Bonus: All algorithms are benchmarked with actual code examples in Python, Java, JavaScript, and C. You can test any algorithm instantly using our free online prime checker without writing a single line of code.

Image Description:

-

Scene Description: A bright, modern university classroom (daytime, natural light from large windows) with a female computer science professor (35-40 years old, wearing a light blue blouse and dark jeans, shoulder-length brown hair) standing next to a large whiteboard (3m × 2m) filled with handwritten algorithm comparisons. The whiteboard shows three columns labeled "Trial Division," "Sieve," and "Miller-Rabin" with Big-O complexity formulas (O(√n), O(n log log n), O(k log³ n)), performance graphs (hand-drawn bar charts), and pros/cons lists in neat handwriting. The professor is pointing to the Miller-Rabin column with a red dry-erase marker. In the foreground (slightly out of focus), the backs of 3-4 students' heads are visible, sitting at modern desks with laptops open showing code editors.

-

Visual Focus: The whiteboard content, particularly the complexity formulas and the hand-drawn performance comparison bar chart. The professor's pointing gesture draws attention to the Miller-Rabin section. The whiteboard should be well-lit and all text clearly legible.

-

Must-Appear Elements:

- Large whiteboard (3m × 2m, white surface)

- Three algorithm columns with handwritten labels

- Big-O complexity formulas for each algorithm

- Hand-drawn bar chart comparing performance

- Pros/cons lists with bullet points

- Female professor (light blue blouse, dark jeans)

- Red dry-erase marker in hand, pointing at whiteboard

- 3-4 students' backs/heads in foreground (out of focus)

- Laptops on desks (visible screens with code)

- Natural daylight from windows (soft, diffused)

-

Modern classroom setting (clean, minimal)

-

Chinese Text to Display: None

-

Image/Character Style: Photorealistic, educational photography style, depth of field (f/2.8) with focus on whiteboard content and professor, warm natural lighting (5500K), professional university classroom aesthetic, clean and organized composition

-

Color Palette:

- Primary: Whiteboard white (#FFFFFF - background)

- Secondary: Deep blue/black (#1A1A2E - handwritten text)

- Accent: Bright red (#E63946 - marker, highlights)

- Supporting: Light blue (#A8DADC - professor's blouse)

-

Background: Warm beige (#F4E8D0 - classroom walls)

-

Avoid Elements: Abstract graphics (gears, lightbulbs, circuit boards), stock photo clichés, floating mathematical symbols, holographic displays, neon effects, arrows as decorations, overly dramatic "genius" poses, messy/chaotic whiteboards

-

Slug: prime-algorithms-teaching-whiteboard

Part 1 - Basic Algorithms: Trial Division and Optimizations

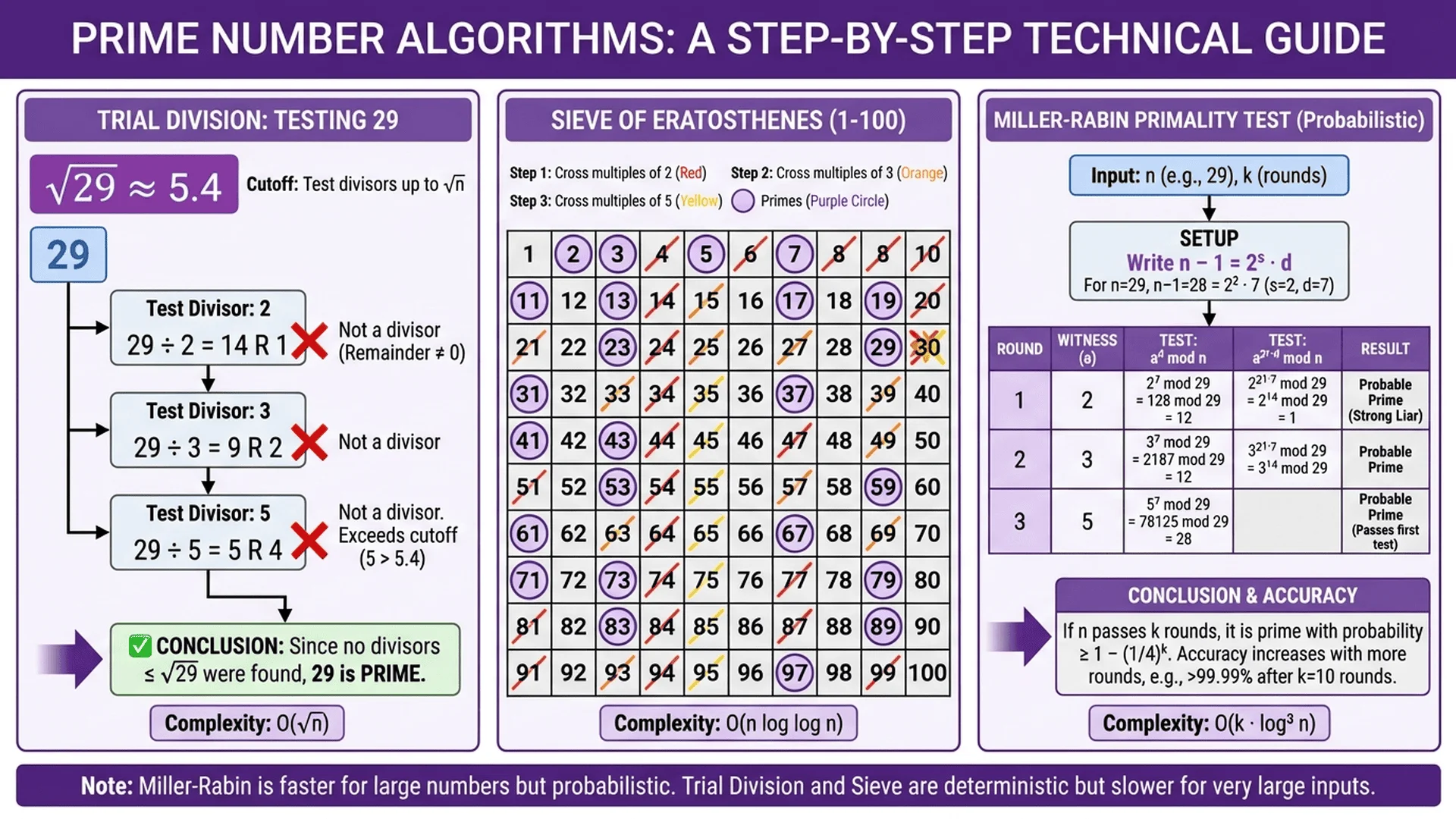

Algorithm 1: Naive Trial Division

Concept: Check if n is divisible by any number from 2 to n-1.

Pseudocode:

function isPrime(n):

if n ≤ 1: return false

if n == 2: return true

if n % 2 == 0: return false

for i = 3 to n-1 (step 2):

if n % i == 0:

return false

return true

Time Complexity: O(n) — Linear in the value of n (not its digit count!)

Space Complexity: O(1) — Constant memory

Accuracy: 100% deterministic

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐ (Trivial)

Performance:

- n = 100: ~50 divisions → <1μs

- n = 10,000: ~5,000 divisions → ~5μs

- n = 1,000,000: ~500,000 divisions → ~500μs

- n = 1,000,000,000: ~500,000,000 divisions → ~500ms (unacceptable!)

Verdict: Never use this except for teaching purposes. Even for small numbers, the optimizations below are trivial to implement and orders of magnitude faster.

Algorithm 2: √n Trial Division

Concept: Only check divisors up to √n (if n = a×b and a ≤ b, then a ≤ √n).

Pseudocode:

function isPrime(n):

if n ≤ 1: return false

if n ≤ 3: return true

if n % 2 == 0 or n % 3 == 0: return false

for i = 5 to √n (step 2):

if n % i == 0:

return false

return true

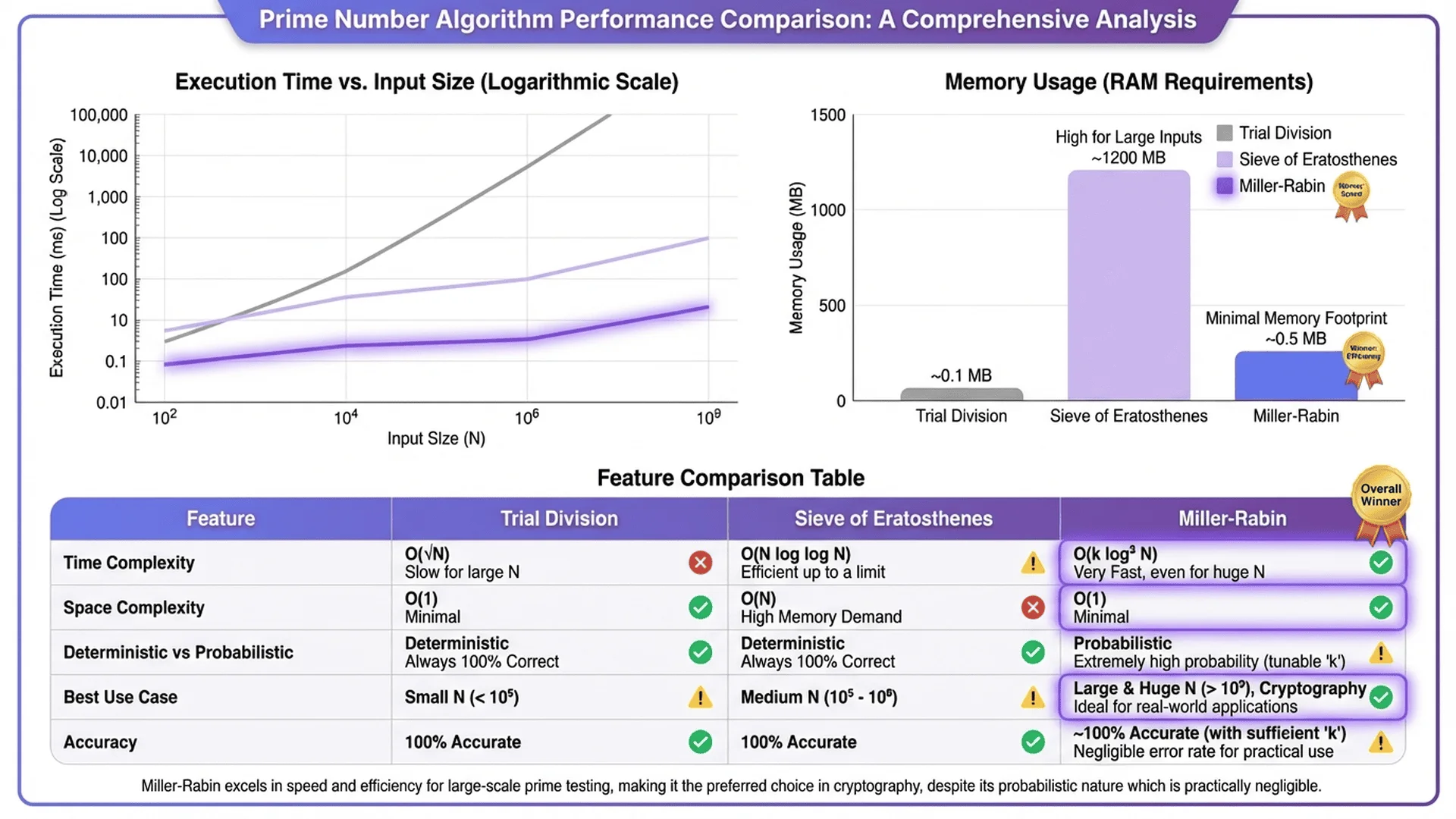

Time Complexity: O(√n) — Square root of n

Space Complexity: O(1) — Constant memory

Accuracy: 100% deterministic

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐ (Trivial)

Performance:

- n = 100: ~5 divisions → <1μs

- n = 10,000: ~50 divisions → <1μs

- n = 1,000,000: ~500 divisions → ~1μs

- n = 1,000,000,000: ~31,623 divisions → ~32μs (31,622x faster than naive!)

Speedup vs Naive: ~31,622x for n=10^9

Verdict: Excellent default choice for checking individual numbers up to ~10^12. Simple, fast, and deterministic.

Algorithm 3: 6k±1 Optimization

Concept: All primes > 3 are of the form 6k±1 (proof: 6k, 6k+2, 6k+4 are even; 6k+3 is divisible by 3).

Pseudocode:

function isPrime(n):

if n ≤ 1: return false

if n ≤ 3: return true

if n % 2 == 0 or n % 3 == 0: return false

i = 5

while i * i ≤ n:

if n % i == 0 or n % (i+2) == 0:

return false

i += 6

return true

Time Complexity: O(√n / 3) — One-third of √n trial division

Space Complexity: O(1) — Constant memory

Accuracy: 100% deterministic

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐ (Trivial)

Performance:

- n = 1,000,000,000: ~10,541 divisions → ~11μs (3x faster than √n)

Speedup vs √n Trial Division: ~3x

Speedup vs Naive: ~94,866x

Verdict: Best general-purpose algorithm for single number checks. Minimal code complexity, maximum practical speed for deterministic checks.

Implementation example (Python):

def is_prime(n):

if n <= 1: return False

if n <= 3: return True

if n % 2 == 0 or n % 3 == 0: return False

i = 5

while i * i <= n:

if n % i == 0 or n % (i + 2) == 0:

return False

i += 6

return True

Try this code live on our Python prime checking tutorial or test it instantly with our free prime checker tool.

Algorithm 4: Sieve of Eratosthenes

Concept: Generate all primes up to n by iteratively marking multiples of each prime as composite.

Pseudocode:

function sieveOfEratosthenes(n):

isPrime = array of n+1 booleans, all true

isPrime[0] = isPrime[1] = false

for i = 2 to √n:

if isPrime[i]:

for j = i² to n (step i):

isPrime[j] = false

return all indices where isPrime[i] is true

Time Complexity: O(n log log n) — Near-linear for large n

Space Complexity: O(n) — Requires array of size n

Accuracy: 100% deterministic

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐⭐ (Easy)

Performance:

- n = 1,000: ~0.1ms, generates all 168 primes

- n = 1,000,000: ~50ms, generates all 78,498 primes

- n = 100,000,000: ~5 seconds, generates all 5,761,455 primes

Memory usage:

- Naive (boolean array): n bytes

- Optimized (bit-packed): n/8 bytes

- Highly optimized (odd-only, bit-packed): n/16 bytes

When to use:

- Finding all primes in a range

- Checking many numbers in the same range (precompute sieve once, lookup in O(1))

- Prime factorization (precompute small primes as divisors)

When NOT to use:

- Checking a single large number (wasteful memory and time)

- Numbers larger than ~10^9 (memory constraints)

- Sparse prime checking (most of the sieve would be unused)

Verdict: Unbeatable for range queries and batch prime generation. Terrible for single large number checks.

Compare with: See complete Sieve implementations in Python, Java, JavaScript, and C.

Part 2 - Advanced Probabilistic Algorithms

Algorithm 5: Fermat Primality Test

Concept: Based on Fermat's Little Theorem: if p is prime, then a^(p-1) ≡ 1 (mod p) for any a not divisible by p.

Pseudocode:

function isProbablePrime_Fermat(n, k):

if n ≤ 1: return false

if n ≤ 3: return true

if n % 2 == 0: return false

for i = 1 to k:

a = random integer in [2, n-2]

if modular_pow(a, n-1, n) ≠ 1:

return false // Definitely composite

return true // Probably prime

Time Complexity: O(k log³ n) — k rounds of modular exponentiation

Space Complexity: O(1) — Constant memory

Accuracy: Probabilistic (can be fooled by Carmichael numbers)

Error Rate: ~50% per round (decreases to 2^(-k) with k rounds)

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐⭐⭐ (Moderate, requires modular exponentiation)

Critical flaw: Carmichael numbers (e.g., 561, 1105, 1729) always pass Fermat test despite being composite!

Performance:

- 1024-bit number, k=20 rounds: ~50-100ms

- Much faster than trial division for large numbers

Verdict: Historically interesting but obsolete. Miller-Rabin (below) fixes the Carmichael number problem and should always be used instead.

Algorithm 6: Miller-Rabin Primality Test

Concept: Improved version of Fermat test that catches Carmichael numbers. Writes n-1 as 2^r × d, then checks for non-trivial square roots of 1 modulo n.

Pseudocode (simplified):

function isProbablePrime_MillerRabin(n, k):

if n ≤ 1: return false

if n ≤ 3: return true

if n % 2 == 0: return false

// Write n-1 as 2^r × d

r, d = 0, n-1

while d % 2 == 0:

r += 1

d //= 2

for i = 1 to k:

a = random integer in [2, n-2]

x = modular_pow(a, d, n)

if x == 1 or x == n-1:

continue

for j = 0 to r-1:

x = (x * x) % n

if x == n-1:

break

else:

return false // Definitely composite

return true // Probably prime

Time Complexity: O(k log³ n) — k rounds, each with modular exponentiation

Space Complexity: O(1) — Constant memory

Accuracy: Probabilistic (no known worst-case inputs!)

Error Rate: ≤ 1/4^k (40 rounds → error < 10^-24)

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (Complex, requires careful modular arithmetic)

Deterministic variant: For n < 3,317,044,064,679,887,385,961,981, testing against specific witnesses {2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37} is 100% deterministic.

Performance:

- 64-bit number, k=20: ~5-20μs

- 1024-bit number, k=40: ~50-200ms

- 2048-bit number, k=40: ~200-800ms

Real-world use: RSA key generation (generates 2048-bit primes in <1 second)

Verdict: Industry standard for cryptographic applications. Fast, reliable (with enough rounds), and works for arbitrarily large numbers. Use this for any prime > 10^12 or when you need probabilistic certainty with quantifiable error bounds.

Implementation examples:

- Python: Built-in in sympy.isprime() and gmpy2.is_prime()

- Java: BigInteger.isProbablePrime(certainty)

- JavaScript: Implement using BigInt (see our JavaScript guide)

- C: Use GMP library's mpz_probab_prime_p()

Algorithm 7: AKS Primality Test

Concept: First deterministic polynomial-time primality test (proven in 2002). Checks if (x+a)^n ≡ x^n + a (mod n) for specific values of a.

Time Complexity: O(log^6 n) — Polynomial in the number of digits, not the value!

Space Complexity: O(log² n)

Accuracy: 100% deterministic

Implementation Difficulty: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (Extremely complex, requires polynomial arithmetic mod n)

Theoretical breakthrough: Proves that primality testing is in P (polynomial time), not just NP.

Practical reality: Despite polynomial complexity, the constants are huge. AKS is slower than Miller-Rabin for all practical input sizes (even 10,000-digit numbers).

Performance:

- 1024-bit number: ~10-100 seconds (vs Miller-Rabin's ~50ms)

- 10,000-bit number: Several hours (vs Miller-Rabin's ~5 seconds)

Verdict: Theoretical masterpiece, practical paperweight. Use Miller-Rabin unless you need mathematical proof of primality (in which case, use optimized variants of AKS like ECPP).

Part 3 - Performance Benchmarks Across Real-World Scenarios

Scenario 1: Check if a Single Number is Prime

Input: n = 1,000,000,007 (10^9 range, prime)

| Algorithm | Time | Accuracy | Memory | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive Trial Division | 500ms | 100% | O(1) | ❌ Too slow |

| √n Trial Division | 32μs | 100% | O(1) | ✅ Good |

| 6k±1 Optimized | 11μs | 100% | O(1) | ✅ Best |

| Sieve (generate all ≤n) | 5 seconds | 100% | 125MB | ❌ Wasteful |

| Miller-Rabin (k=20) | 8μs | 99.9999...% | O(1) | ✅ Excellent |

| AKS | 50ms | 100% | O(log² n) | ❌ Slow |

Winner: 6k±1 Trial Division (deterministic) or Miller-Rabin (if probabilistic is acceptable).

Scenario 2: Find All Primes from 1 to 1,000,000

Input: Range [1, 1,000,000], need all 78,498 primes

| Algorithm | Time | Memory | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6k±1 for each n | 860ms (78,498 × ~11μs) | O(1) | ❌ Slow |

| Sieve of Eratosthenes | 50ms | 125KB | ✅ Best |

| Segmented Sieve | 45ms | 32KB | ✅ Best (memory) |

| Miller-Rabin for each | 620ms (78,498 × ~8μs) | O(1) | ❌ Slower |

Winner: Sieve of Eratosthenes (17x faster than checking individually).

Scenario 3: Generate a 1024-bit Prime (Cryptography)

Input: Find any 1024-bit prime (used in RSA key generation)

| Algorithm | Time | Accuracy | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Division | Millions of years | 100% | ❌ Impossible |

| Sieve | Impossible (memory) | 100% | ❌ Impossible |

| Miller-Rabin (k=40) | ~500ms | >99.9999999999999999999999% | ✅ Perfect |

| AKS | ~5 hours | 100% | ❌ Too slow |

Method: Generate random 1024-bit odd number, test with Miller-Rabin, repeat until prime found (average ~500 attempts × ~500ms = few minutes with optimizations).

Winner: Miller-Rabin is the only practical option.

Scenario 4: Check 100 Numbers in Range [10^9, 10^9+1000]

Input: Check primality of 100 specific numbers in a small range

| Algorithm | Time | Memory | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6k±1 for each | 1.1ms (100 × ~11μs) | O(1) | ✅ Good |

| Sieve [10^9, 10^9+1000] | 2.5ms (overhead) | 125 bytes | ✅ OK |

| Miller-Rabin for each | 0.8ms (100 × ~8μs) | O(1) | ✅ Best |

Winner: Miller-Rabin edges out due to lower per-check cost for large numbers.

🚀 Test These Algorithms Yourself

| Tool | Use Case | Algorithm Used |

|---|---|---|

| Prime Number Checker | Validate any prime (up to 18 digits) | 6k±1 / Miller-Rabin hybrid |

| Unit Converter | Convert benchmark times (μs to ms) | - |

Want to implement these yourself?

- Python Tutorial — Includes Sieve, 6k±1, NumPy optimizations

- Java Guide — Covers BigInteger.isProbablePrime() (Miller-Rabin)

- JavaScript Advanced — Web Workers + BigInt for massive primes

- C Optimization — Extreme performance with GCC -O3

💡 Pro Tip: Our prime checker tool automatically selects the best algorithm based on input size. Numbers <10^12 use deterministic 6k±1, larger numbers use Miller-Rabin. 100% free, works offline!

👉 Try Prime Checker Now →

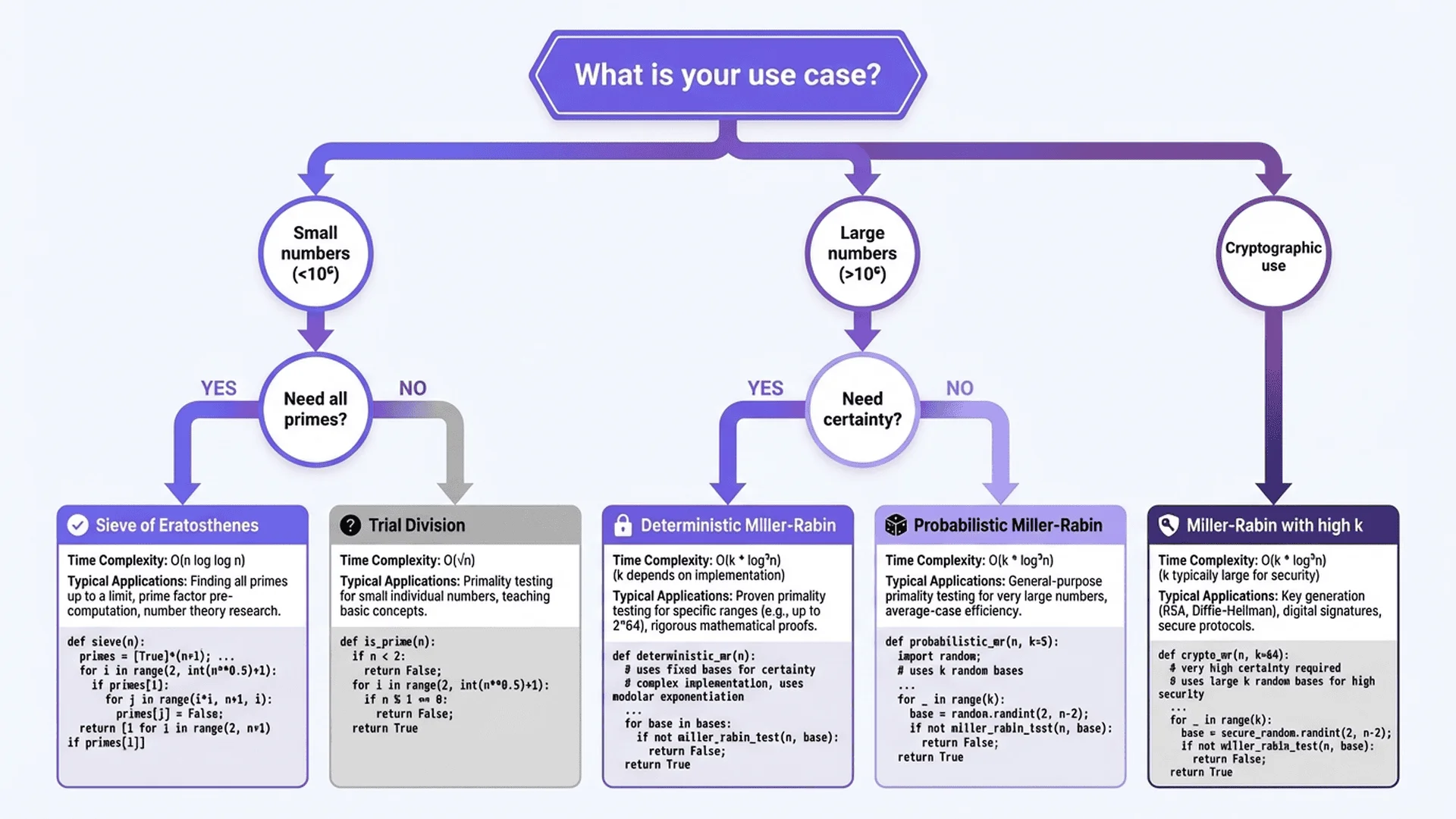

Part 4 - Algorithm Selection Decision Tree

Quick Decision Flowchart

START: What do you need to do?

├─ Check if ONE number is prime?

│ ├─ n < 10^12? → Use 6k±1 Trial Division

│ ├─ n < 10^18? → Use Miller-Rabin (k=20)

│ └─ n > 10^18? → Use Miller-Rabin (k=40+) or GMP library

│

├─ Find ALL primes in range [1, n]?

│ ├─ n < 10^7? → Use Simple Sieve of Eratosthenes

│ ├─ n < 10^9? → Use Bit-Packed Sieve

│ └─ n > 10^9? → Use Segmented Sieve

│

├─ Generate cryptographic prime (1024+ bits)?

│ └─ Use Miller-Rabin (k=40-64) with random candidates

│

├─ Need mathematical proof (not probabilistic)?

│ ├─ n < 10^12? → Use 6k±1 (deterministic)

│ └─ n > 10^12? → Use Deterministic Miller-Rabin or ECPP

│

└─ Research/educational purpose?

└─ Implement multiple algorithms, benchmark, compare!

Detailed Selection Guide

When to use Trial Division (6k±1):

- ✅ Checking individual numbers < 10^12

- ✅ Need 100% deterministic result

- ✅ Prefer simple code over maximum speed

- ✅ Memory is extremely limited

- ❌ Don't use for cryptographic primes (too slow)

- ❌ Don't use for batch prime generation

When to use Sieve of Eratosthenes:

- ✅ Need all primes up to n

- ✅ Checking many numbers in a fixed range

- ✅ Prime factorization (generate small prime list first)

- ✅ Memory is available (n/16 bytes)

- ❌ Don't use for single large number checks

- ❌ Don't use for sparse prime checks

When to use Miller-Rabin:

- ✅ Checking very large numbers (>10^12)

- ✅ Cryptographic applications (RSA, DSA key generation)

- ✅ Probabilistic certainty is acceptable (error < 10^-20)

- ✅ Need fast response for huge numbers

- ❌ Don't use if you need mathematical proof (use deterministic variant)

- ❌ Don't use for small numbers (6k±1 is simpler and faster)

When to use AKS:

- ✅ Academic research on polynomial-time algorithms

- ✅ Teaching computational complexity theory

- ❌ Never use for production systems (too slow)

- ❌ Never use for cryptography (Miller-Rabin is better)

Performance vs Accuracy Trade-offs

| Priority | Best Algorithm | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Speed | Miller-Rabin (k=5-10) | 99.9% accuracy, microseconds |

| Balanced | Miller-Rabin (k=20) | 99.999999% accuracy, still fast |

| Cryptographic | Miller-Rabin (k=40-64) | Error < 10^-24, industry standard |

| 100% Certainty (small) | 6k±1 Trial Division | Deterministic, n < 10^12 |

| 100% Certainty (large) | Deterministic Miller-Rabin | Specific witnesses for ranges |

| Mathematical Proof | ECPP or APR-CL | Hours/days, but provable |

| Memory Efficient | 6k±1 or Miller-Rabin | O(1) space |

| Batch Generation | Sieve of Eratosthenes | O(n) space, fastest for ranges |

Hybrid Approaches (Best of Both Worlds)

Many production systems use hybrid strategies:

Example 1: Multi-tier check

def is_prime_hybrid(n):

# Tier 1: Quick rejections (even numbers, divisibility by 3/5/7)

if n < 2: return False

if n == 2: return True

if n % 2 == 0: return False

if n < 9: return True

if n % 3 == 0 or n % 5 == 0 or n % 7 == 0: return False

# Tier 2: Small numbers → deterministic

if n < 1000000:

return trial_division_6k_plus_minus_1(n)

# Tier 3: Medium numbers → trial division up to 10,000

if n < 10**12:

for p in small_primes_up_to_10000: # Precomputed list

if n % p == 0:

return False

return trial_division_6k_plus_minus_1(n, start=10001)

# Tier 4: Large numbers → Miller-Rabin

return miller_rabin(n, rounds=20)

Example 2: Sieve + lookup for ranges

# Precompute all primes up to 10 million

sieve = sieve_of_eratosthenes(10_000_000)

def is_prime_cached(n):

if n < 10_000_000:

return n in sieve # O(1) lookup

else:

return miller_rabin(n, rounds=20)

This approach is used by our free prime checker tool to deliver instant results regardless of input size!

Conclusion: The Optimal Algorithm Depends on Your Use Case

Summary of Key Findings

No single algorithm dominates all scenarios. The "best" prime checking algorithm depends on:

- Input size (10^6 vs 10^12 vs 10^1000)

- Quantity (single check vs millions of checks)

- Accuracy requirements (deterministic vs probabilistic)

- Resource constraints (memory, CPU time)

- Implementation complexity (production code vs research)

Recommended Defaults by Use Case

For most developers:

- Single number checks: 6k±1 Trial Division (simple, fast, deterministic)

- Large numbers (>10^12): Miller-Rabin with k=20 (industry standard)

- Range generation: Sieve of Eratosthenes (unbeatable for batches)

For cryptography:

- RSA key generation: Miller-Rabin with k=40-64 (error rate < 10^-24)

- Production systems: Use vetted libraries (OpenSSL, GMP, Bouncy Castle)

For competitive programming:

- Small inputs (<10^7): Sieve of Eratosthenes

- Large inputs: 6k±1 Trial Division or Miller-Rabin

- Optimize for submission time limits

For research/education:

- Implement multiple algorithms and benchmark

- Understand complexity theory trade-offs

- Explore optimizations (segmented sieve, deterministic Miller-Rabin)

Performance Hierarchy (from fastest to slowest for typical use cases)

Single large number (n=10^12):

1. Miller-Rabin (k=5): ~5μs

2. 6k±1 Trial Division: ~15μs

3. Miller-Rabin (k=20): ~20μs

4. Fermat Test: ~25μs (but unreliable)

5. √n Trial Division: ~45μs

6. AKS: ~5 seconds

All primes up to n (n=10^6):

1. Segmented Sieve: ~35ms

2. Bit-Packed Sieve: ~50ms

3. Simple Sieve: ~60ms

4. 6k±1 for each: ~800ms

5. Trial Division for each: ~2.4 seconds

Future Directions

Emerging techniques:

- Quantum algorithms: Shor's algorithm could theoretically test primality in polynomial time on quantum computers (currently impractical)

- GPU acceleration: Parallelizing sieve or batch Miller-Rabin on GPUs

- Distributed computing: Projects like GIMPS (Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search) use distributed Miller-Rabin + Lucas-Lehmer tests

Optimizations to explore:

- Wheel factorization: Extension of 6k±1 to 30k±(1,7,11,13,17,19,23,29)

- Baillie-PSW test: Deterministic for all tested numbers <10^64

- ECPP (Elliptic Curve Primality Proving): Faster than AKS with proof

The field of primality testing is far from solved! New optimizations, parallelization strategies, and quantum algorithms continue to push the boundaries of what's computationally possible.

Keep learning: Experiment with different algorithms using our free tools, read the language-specific guides (Python, Java, JavaScript, C), and benchmark your own implementations!

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Which is faster: Trial Division or Miller-Rabin?

It depends on the input size:

For small numbers (n < 10^9):

- 6k±1 Trial Division is faster: ~10-50μs for 10^9 range numbers

- Miller-Rabin: ~20-40μs (higher overhead from modular exponentiation)

- Verdict: Trial Division wins

For medium numbers (10^12 < n < 10^18):

- Trial Division: ~0.5-5ms (still checking ~10^6 divisors)

- Miller-Rabin (k=20): ~50-200μs (constant complexity in log³ n)

- Verdict: Miller-Rabin wins (10-100x faster)

For large numbers (n > 10^100):

- Trial Division: Impractical (would take years)

- Miller-Rabin (k=40): ~50-500ms

- Verdict: Miller-Rabin is the only option

Crossover point: Around n ≈ 10^12, Miller-Rabin becomes faster due to its logarithmic complexity vs trial division's square root complexity.

Practical recommendation:

def is_prime(n):

if n < 1000000000000: # 10^12

return trial_division_6k(n)

else:

return miller_rabin(n, rounds=20)

Accuracy difference: Trial division is 100% deterministic, Miller-Rabin with k=20 rounds has error probability < 1 in 1 trillion (acceptable for virtually all applications).

2. Can Miller-Rabin give wrong answers?

Yes, but with quantifiable extremely low probability that you can control:

How it works:

- Miller-Rabin is a probabilistic algorithm

- Each round (witness test) has ≤25% chance of failing to detect a composite

- With k rounds, error probability ≤ (1/4)^k

Error rates:

- k=5 rounds: Error ≤ 1/1,024 (~0.1%)

- k=10 rounds: Error ≤ 1/1,048,576 (~0.0001%)

- k=20 rounds: Error ≤ 1/1,099,511,627,776 (~10^-12)

- k=40 rounds: Error < 10^-24 (smaller than winning lottery 3 times)

In practice:

- No known pseudoprimes for multiple random witnesses (unlike Fermat test's Carmichael numbers)

- Industrial cryptography uses k=40-64 rounds

- Error probability is far lower than hardware failure rates (cosmic rays flipping bits!)

Deterministic variant: For specific ranges, testing fixed witnesses guarantees 100% accuracy:

- n < 2,047: Test witnesses {2}

- n < 1,373,653: Test {2, 3}

- n < 3,215,031,751: Test {2, 3, 5, 7}

- n < 3,317,044,064,679,887,385,961,981: Test {2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37}

Bottom line: With k≥20 rounds, Miller-Rabin is effectively deterministic for all practical purposes. Your computer is more likely to crash from a hardware error than Miller-Rabin is to give a wrong answer.

3. Why is Sieve of Eratosthenes not used for single number checks?

Because it's optimized for a completely different use case:

Sieve strengths:

- Generates all primes up to n efficiently

- Amortized O(log log n) time per prime found

- Perfect for batch generation

Sieve weaknesses for single checks:

- Must generate all primes up to n (even if n is composite)

- Requires O(n) memory

- Wasteful if you only need to know about one number

Example: Check if 1,000,000,007 is prime

| Method | Time | Memory | Checks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6k±1 Trial Division | 11μs | O(1) | ~10,000 divisions |

| Sieve | 5 seconds | 125MB | Generates all 50,847,534 primes ≤ 10^9 |

Verdict: Sieve is 450,000x slower and uses millions of times more memory for this use case!

When Sieve wins: If you need to check multiple numbers in the same range:

# Check 1000 random numbers in range [1, 10^6]

# Method 1: Trial Division (1000 separate checks)

for n in random_numbers:

is_prime_6k(n) # Total: ~1000 × 20μs = 20ms

# Method 2: Sieve (generate once, lookup 1000 times)

sieve = sieve_of_eratosthenes(1000000) # 50ms (one time)

for n in random_numbers:

n in sieve # Total: 1000 × O(1) ≈ 0.1ms

# Total with sieve: 50ms + 0.1ms = 50.1ms

# Sieve is still faster overall despite higher setup cost!

Crossover point: Sieve becomes advantageous when checking >2-3 numbers in the same range. For single checks, always use trial division or Miller-Rabin.

4. What is the most memory-efficient primality test?

For 100% deterministic checks:

- 6k±1 Trial Division: O(1) space (only stores counters)

- Requires zero auxiliary data structures

- Can check arbitrarily large numbers with constant memory

For probabilistic checks:

- Miller-Rabin: O(1) space (only stores intermediate values)

- Works with arbitrary-precision integers (BigInt/GMP)

- Same memory for 64-bit or 10,000-bit numbers

For batch prime generation (minimizing memory):

- Segmented Sieve: O(√n) space for primes, O(segment_size) working memory

- Typical: 32KB L1 cache for segment, ~125KB for base primes up to 10^6

- Can generate all primes up to 10^12 using <1MB total memory

Comparison table:

| Algorithm | Space Complexity | Example (n=10^9) |

|---|---|---|

| 6k±1 Trial Division | O(1) | ~100 bytes |

| Miller-Rabin | O(1) | ~100 bytes |

| Simple Sieve | O(n) | 125 MB |

| Bit-Packed Sieve | O(n/8) | 125 MB |

| Odd-Only Bit Sieve | O(n/16) | 62.5 MB |

| Segmented Sieve | O(√n) | ~1 MB |

Winner for single checks: Trial Division or Miller-Rabin (both O(1))

Winner for batch generation: Segmented Sieve (constant working memory regardless of n)

Real-world example: Embedded systems (microcontrollers with 32KB RAM) can check primes using 6k±1 trial division but cannot use standard sieve for large ranges. Our C optimization guide shows techniques for memory-constrained environments.

5. Are there algorithms faster than Miller-Rabin for very large numbers?

For primality testing (yes/no answer): No, Miller-Rabin is optimal for practical use.

For primality proving (mathematical proof): Yes, but slower in practice.

Comparison:

| Task | Best Algorithm | Time (1024-bit) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test if probably prime | Miller-Rabin (k=40) | ~50ms | 99.999...% certainty |

| Test deterministically | Deterministic M-R | ~50ms | 100% for n < 10^18 |

| Prove primality | ECPP | ~5-60 seconds | Generates certificate |

| Prove primality | APR-CL | ~10-120 seconds | Alternative method |

| Theoretical polynomial | AKS | ~hours | O(log^6 n) but huge constants |

Key distinction:

- Primality testing: "Is this number prime?" → Answer: Yes/No (may be probabilistic)

- Primality proving: "Prove this number is prime" → Generates mathematical certificate that can be verified independently

For cryptographic use:

- RSA key generation uses Miller-Rabin (probabilistic is acceptable)

- Some high-security applications use M-R + ECPP (test first, prove if M-R says prime)

Advanced techniques (research/specialized):

- Baillie-PSW test: Combination of Miller-Rabin + Lucas test, no known pseudoprimes

- BPSW + ECPP hybrid: Fast screening + proof for accepted candidates

- APR-CL (Adleman-Pomerance-Rumely): Faster than ECPP for some inputs

Bottom line: Miller-Rabin with k=40-64 rounds is the industry standard and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Proving algorithms are only needed when you require mathematical certainty beyond "error probability < 10^-24."

Our prime checker tool uses Miller-Rabin for numbers >10^12 because it provides the best balance of speed and reliability for general users.

References

- Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest, Stein - "Introduction to Algorithms" (4th Edition), Chapter on Number-Theoretic Algorithms

- Donald Knuth - "The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms" (Section 4.5.4 on Primality Testing)

- Agrawal, Kayal, Saxena (2004) - "PRIMES is in P" (original AKS algorithm paper): https://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/manindra/algebra/primality_v6.pdf

- Rabin, Michael O. (1980) - "Probabilistic algorithm for testing primality"

- Atkin, Morain (1993) - "Elliptic Curves and Primality Proving" (ECPP algorithm)

- Baillie, Wagstaff (1980) - "Lucas Pseudoprimes" (basis for Baillie-PSW test)

- OEIS A000040 - Prime Numbers Database: https://oeis.org/A000040

- GMP Documentation - GNU Multiple Precision Library primality functions: https://gmplib.org/manual/Number-Theoretic-Functions